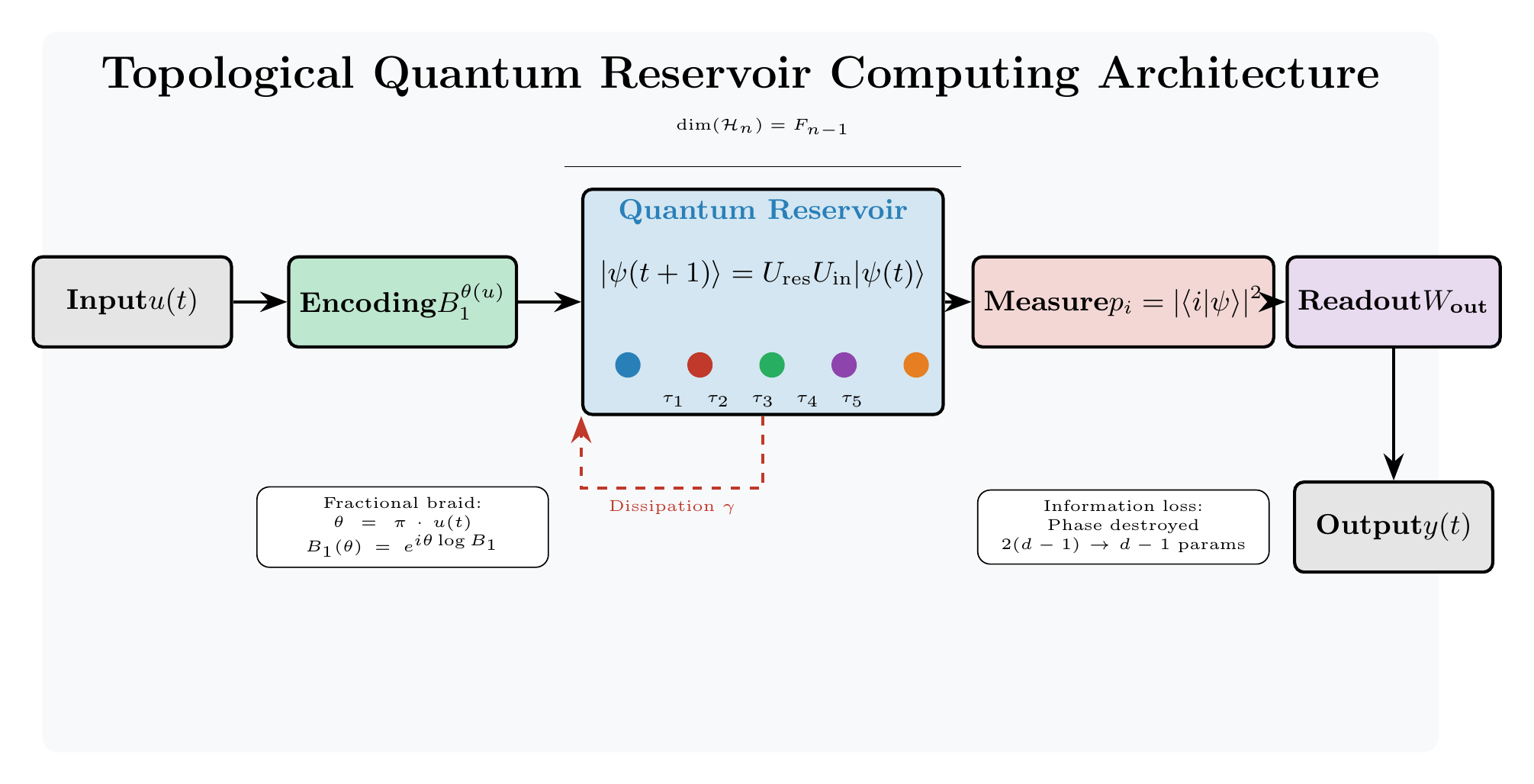

The Fundamental Tension in Topological Quantum Reservoir Computing

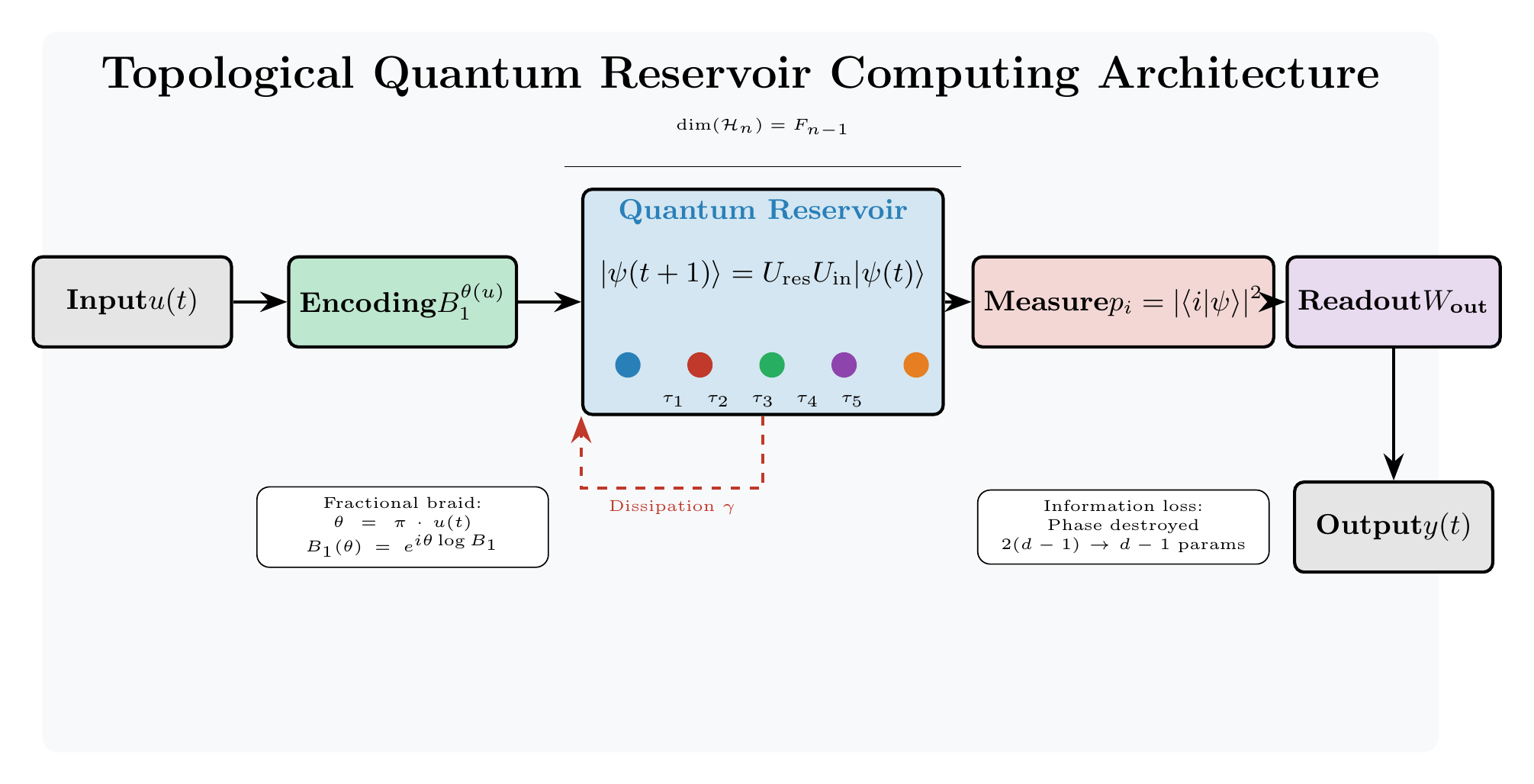

Topological quantum computing promises fault-tolerant quantum operations protected by the geometry of space itself. Reservoir computing promises powerful machine learning without complex training. What happens when you combine them?

Nothing good, as it turns out. In this paper, we prove a fundamental no-go theorem: the properties that make topological systems attractive for quantum computing are exactly what makes them impossible to use as reservoirs.

This is not an engineering problem to be solved with better technology. It is a mathematical incompatibility rooted in the foundations of quantum mechanics.

Version 3.1 Update (January 21, 2026): Language revision following peer review. Reframed TQRC vs ESN comparison as baseline demonstration rather than competition (ESN satisfies ESP by design; TQRC cannot due to unitarity) and improved scientific neutrality throughout. Repository reorganized with proper archival structure. See GitHub commit.

Version 3 Update (January 21, 2026): Enhanced repository infrastructure including GitHub Actions CI/CD, CITATION.cff for proper attribution, and comprehensive reproducibility improvements. The paper now includes explicit limitations discussion in Section 5.5, complete figure cross-references throughout, and additional QRC comparison literature. All scientific claims have been fact-checked against current literature.

Version 2 Update (January 2026): Added 30-trial statistical validation, bootstrap 95% confidence intervals, quantum state evolution visualizations (Figure 9), NARMA-10 benchmark results, and updated literature through 2025 including Google and Quantinuum Fibonacci anyon demonstrations.

What Are Anyons?

To understand our result, we first need to understand the exotic particles called anyons.

In three dimensions, particles come in two types: fermions and bosons. Fermions (like electrons) obey the Pauli exclusion principle. Two fermions cannot occupy the same quantum state. Bosons (like photons) are the opposite. They prefer to bunch together in the same state.

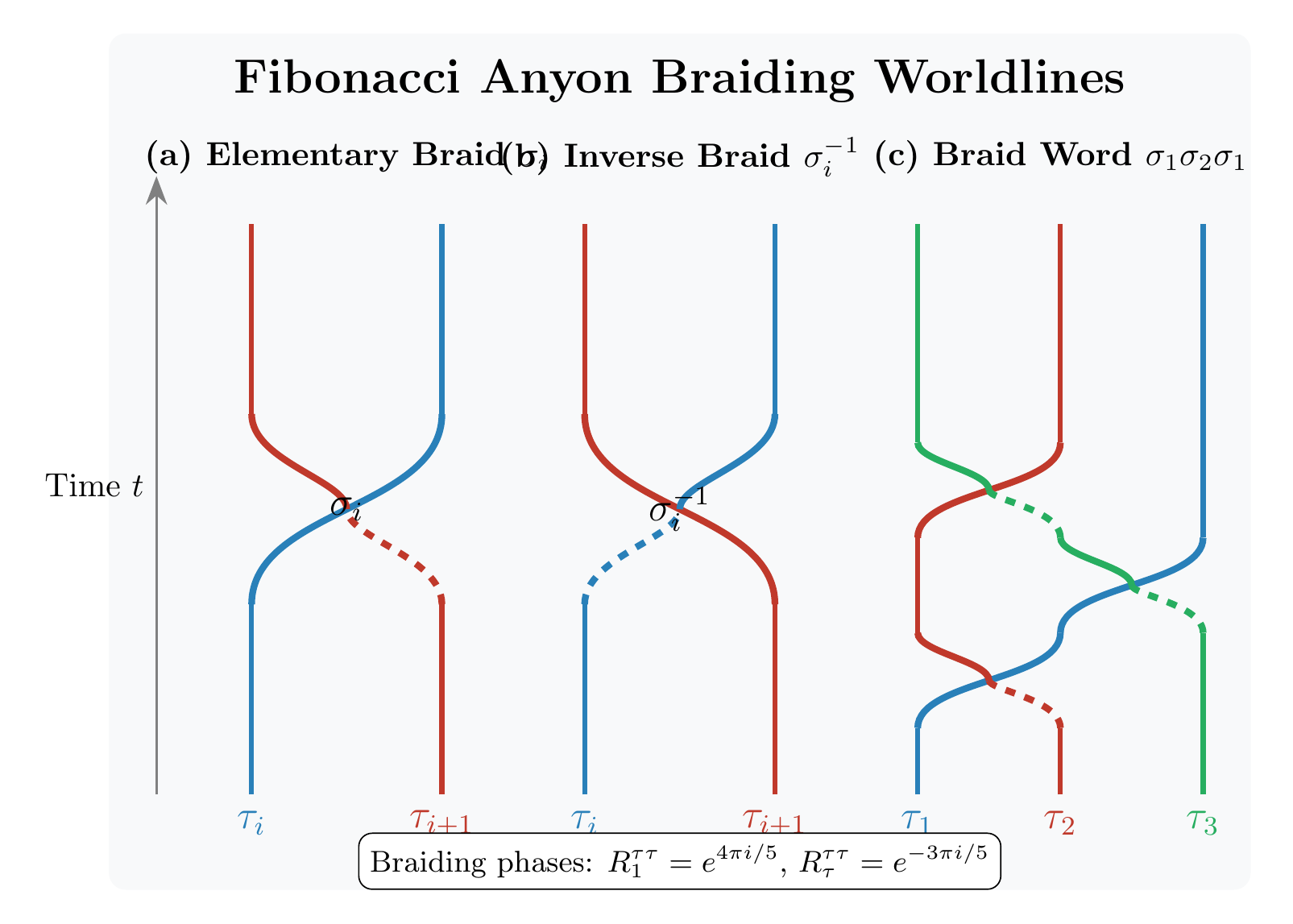

In two dimensions, something remarkable happens. The topology of space allows for particles that are neither fermions nor bosons. These are anyons. When you exchange two anyons by moving them around each other, the quantum state picks up a phase that can be any value between 0 and 2π.

Even more exotic are non-abelian anyons. When you exchange non-abelian anyons, the quantum state does not just pick up a phase. It undergoes a matrix transformation. The order in which you exchange anyons matters. Different exchange sequences produce different quantum states.

This is profoundly different from ordinary particles. Exchanging electrons A and B, then B and C, gives the same result as exchanging B and C first, then A and B. For non-abelian anyons, the order matters.

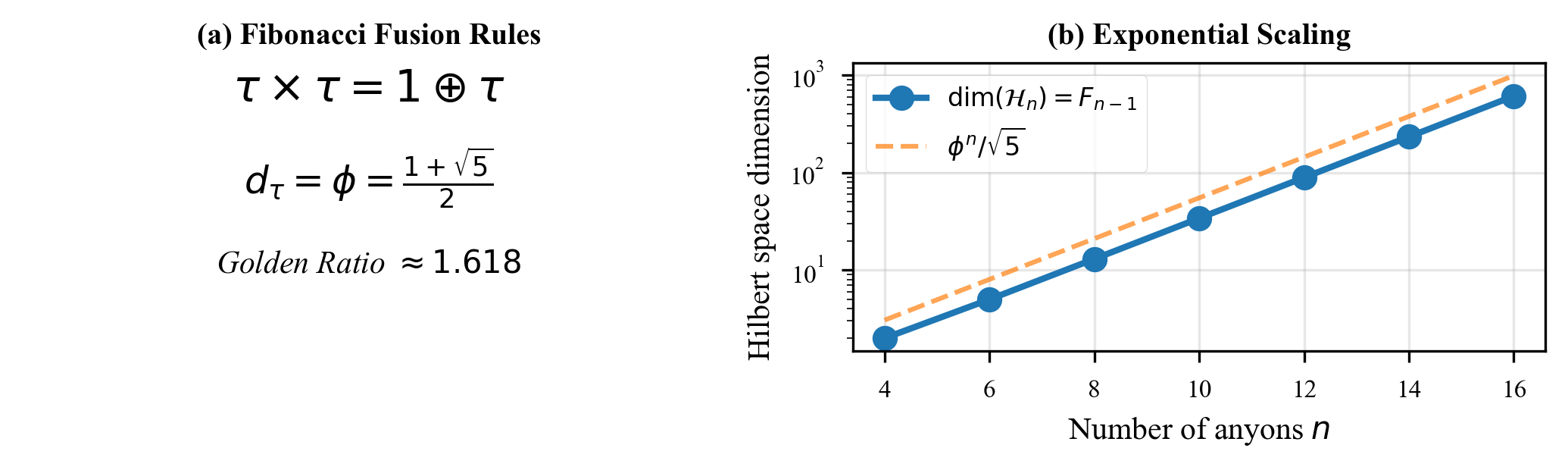

Fibonacci Anyons: The Holy Grail

Among non-abelian anyons, Fibonacci anyons are special. They are “universal” for quantum computation. Any quantum gate can be approximated to arbitrary precision using only Fibonacci anyon braiding operations.

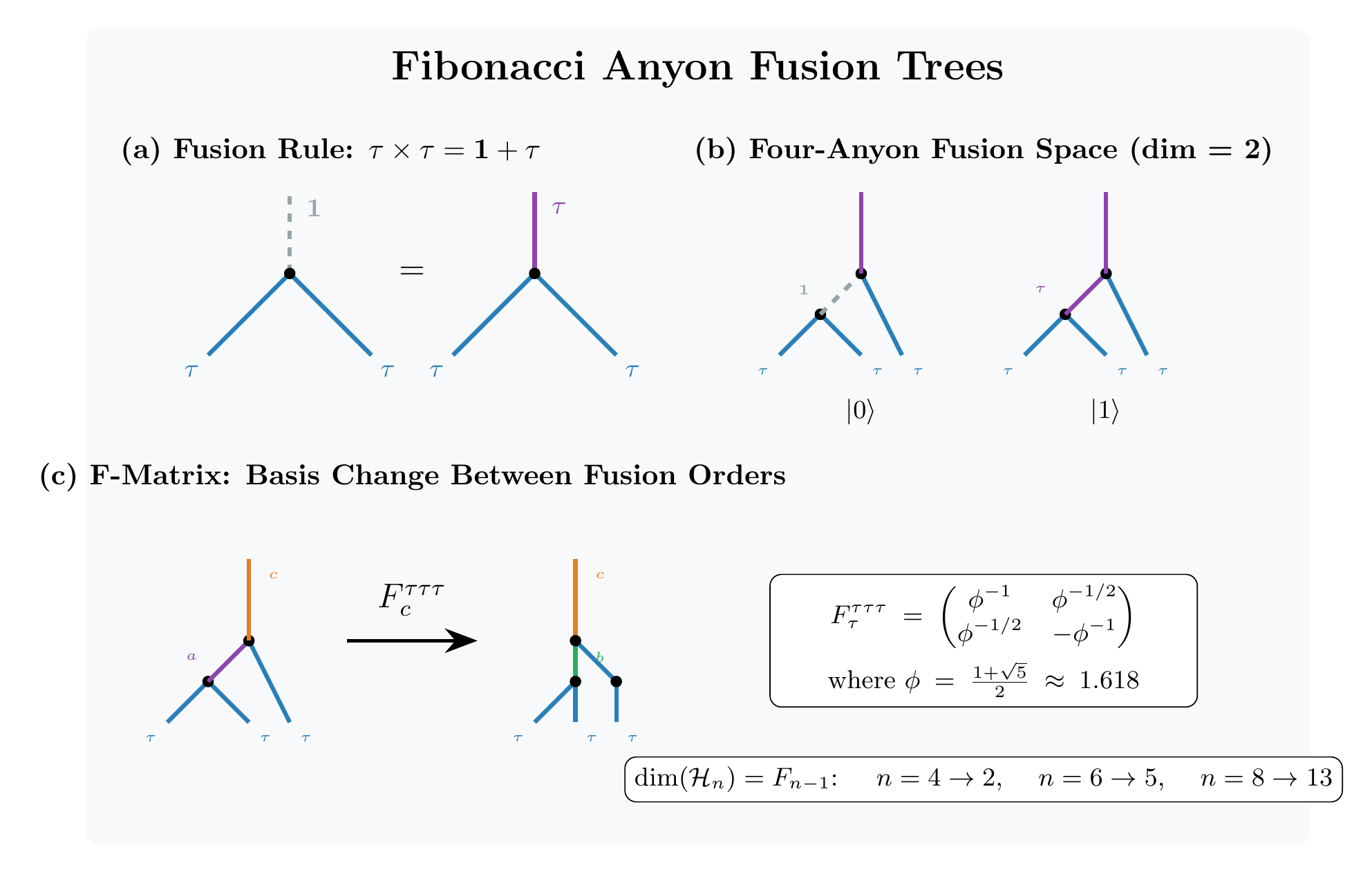

The fusion rules of Fibonacci anyons follow the famous Fibonacci sequence. When two Fibonacci anyons come together, they can fuse into either the vacuum (nothing) or another Fibonacci anyon:

This simple rule encodes profound computational power. The number of states in a system of Fibonacci anyons grows as the th Fibonacci number:

where is the golden ratio. For 100 anyons, this is approximately states.

Why Topological Systems Are Attractive

The appeal of topological quantum computing is error protection. Quantum computers are fragile. Environmental noise, temperature fluctuations, and stray electromagnetic fields all corrupt quantum information.

Traditional quantum error correction requires measuring error syndromes and actively correcting them. This is resource-intensive. Current proposals require many physical qubits for each logical qubit.

Topological systems offer an alternative. The quantum information is encoded in global properties of the system that cannot be affected by local perturbations. No active error correction needed. The physics provides protection automatically.

Braiding Operations Are Unitary

The braiding operations on Fibonacci anyons are exactly unitary. They preserve quantum information perfectly:

Any braiding sequence can be reversed to recover the original state. This is exactly what you want for fault-tolerant quantum gates.

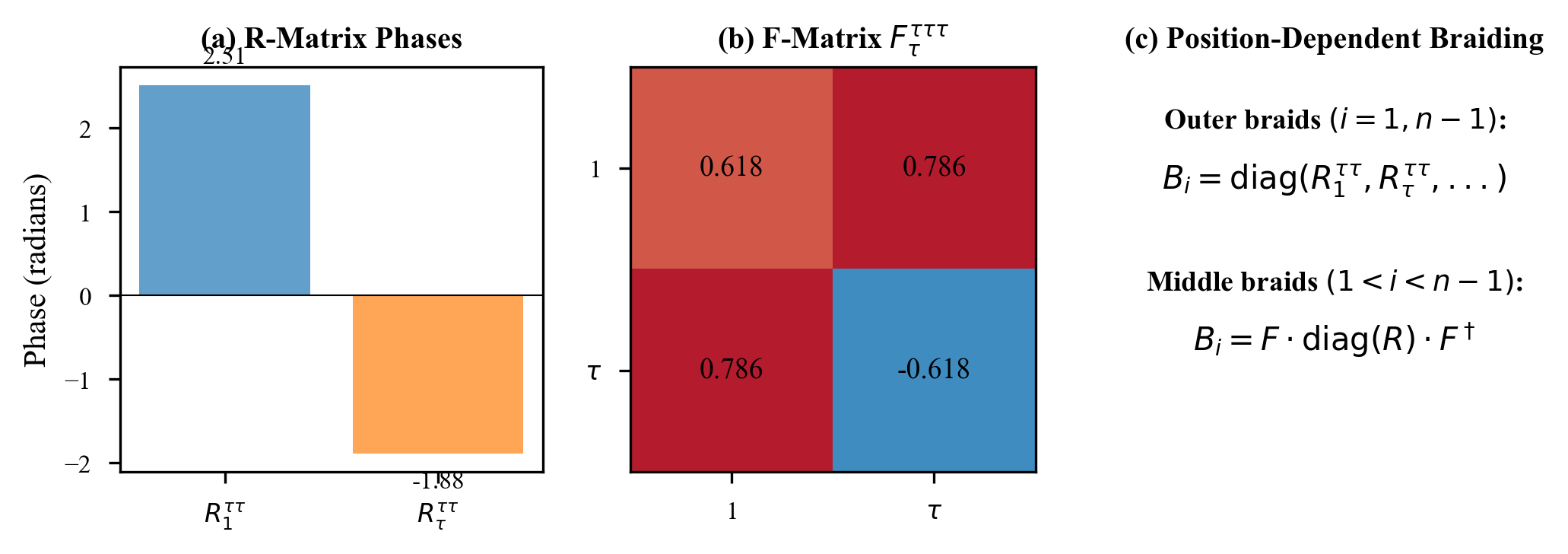

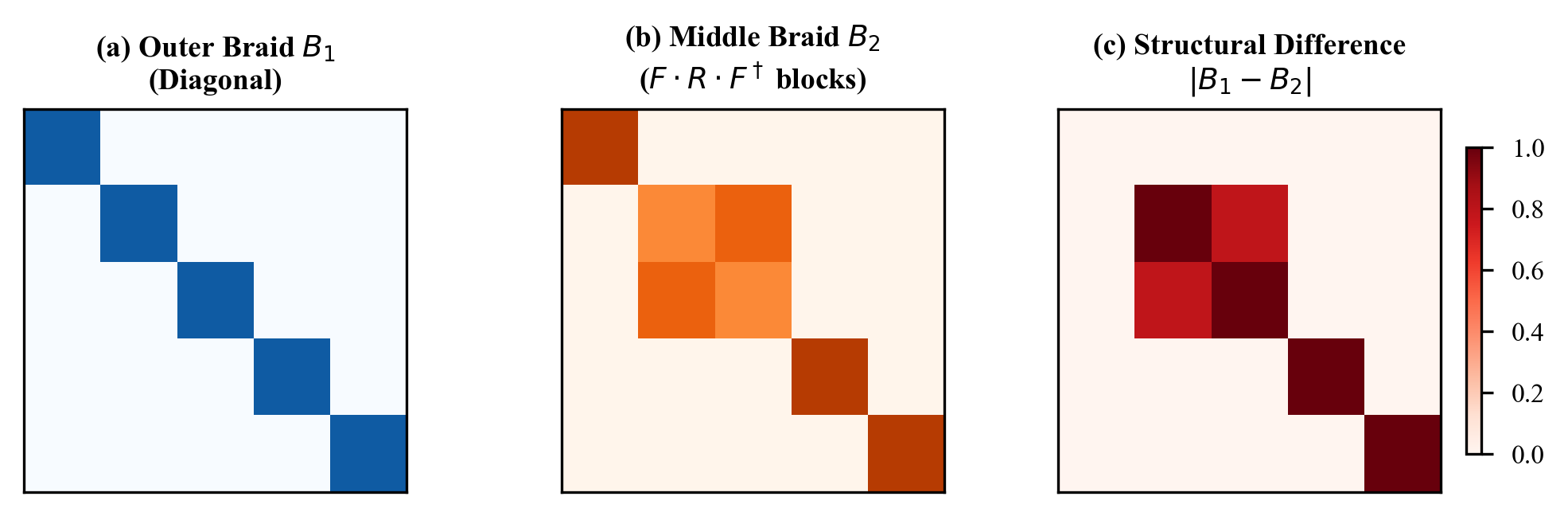

The F and R Matrices

Fibonacci anyon braiding is characterized by two fundamental matrices. The R-matrix describes the phase acquired when exchanging two anyons:

The F-matrix describes the transformation when changing the order of fusion:

where is the golden ratio. Both matrices are unitary.

Table 1: Comparison of Topological vs Non-Topological Quantum Systems

| Property | Topological (Fibonacci Anyons) | Non-Topological (Superconducting) |

|---|---|---|

| Error Protection | Inherent topological protection | Requires active error correction |

| Information Preservation | Perfect (unitary evolution) | Partial (decoherence occurs) |

| Spectral Radius | Exactly 1 | Can be < 1 with dissipation |

| ESP Compatibility | Impossible | Possible with tuning |

| Reservoir Suitability | Not suitable | Well-suited |

| Gate Fidelity | Very high | Moderate |

What is Reservoir Computing?

Reservoir computing emerged from recurrent neural network research. Training recurrent networks is notoriously difficult due to vanishing and exploding gradients. Reservoir computing sidesteps this problem entirely.

The key insight: you do not need to train the recurrent connections. Use any sufficiently complex dynamical system as a “reservoir.” Feed inputs into the reservoir and let it evolve. The reservoir transforms inputs into a high-dimensional feature space. Train only a simple linear readout on top.

The approach works remarkably well for time series prediction, speech recognition, and dynamical system modeling. The reservoir does not need to be carefully designed. Almost any complex nonlinear system works. Even a bucket of water can serve as a reservoir.

Reservoir State Dynamics

The reservoir state evolves according to:

where is the reservoir state, is the input, maps inputs to the reservoir, and is the recurrent weight matrix.

The Echo State Property

For a reservoir to work, it must satisfy the Echo State Property (ESP). This is a technical condition with an intuitive meaning: the reservoir must forget its initial state.

Imagine you start two identical reservoirs in different initial configurations, then feed them the same input sequence. The ESP requires that these reservoirs eventually synchronize. After enough time, they should be in the same state regardless of how they started.

This “fading memory” is essential. Without it, the reservoir’s output would depend on arbitrary details of initialization, not on the input sequence. You could not learn anything meaningful.

Mathematical Definition of ESP

Mathematically, the ESP requires the reservoir’s state transition operator to be contractive:

Different states must get closer together over time.

Spectral Condition for ESP

For linear systems, ESP is equivalent to a spectral condition on the weight matrix:

where is the spectral radius. All eigenvalues must lie strictly inside the unit circle.

Table 2: Echo State Property Requirements

| Requirement | Mathematical Condition | Topological Systems | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| State Convergence | States remain separated | Violated | |

| Spectral Radius | exactly | Violated | |

| Fading Memory | Perfect memory | Violated | |

| Trace Distance Decay | preserved exactly | Violated |

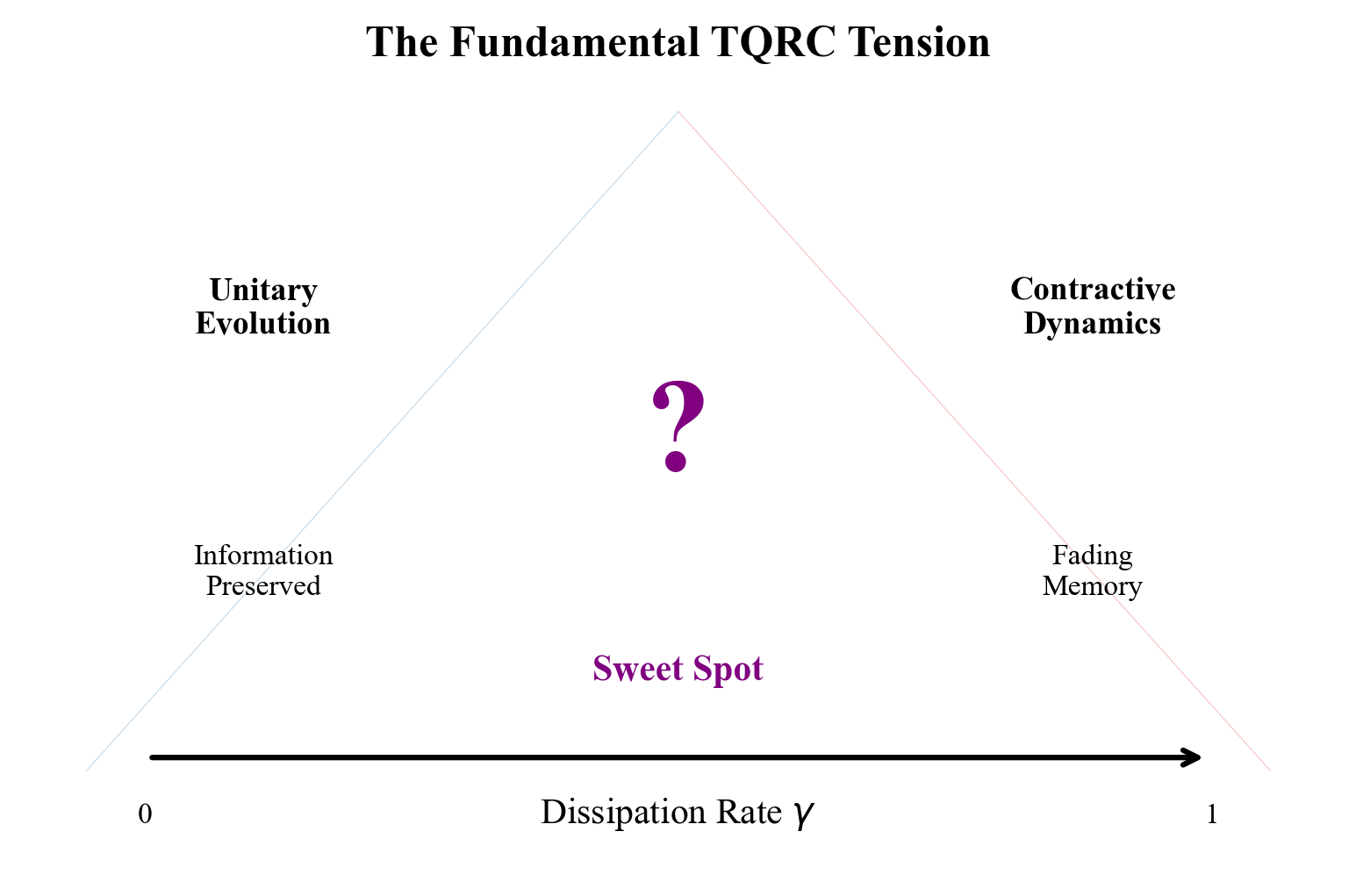

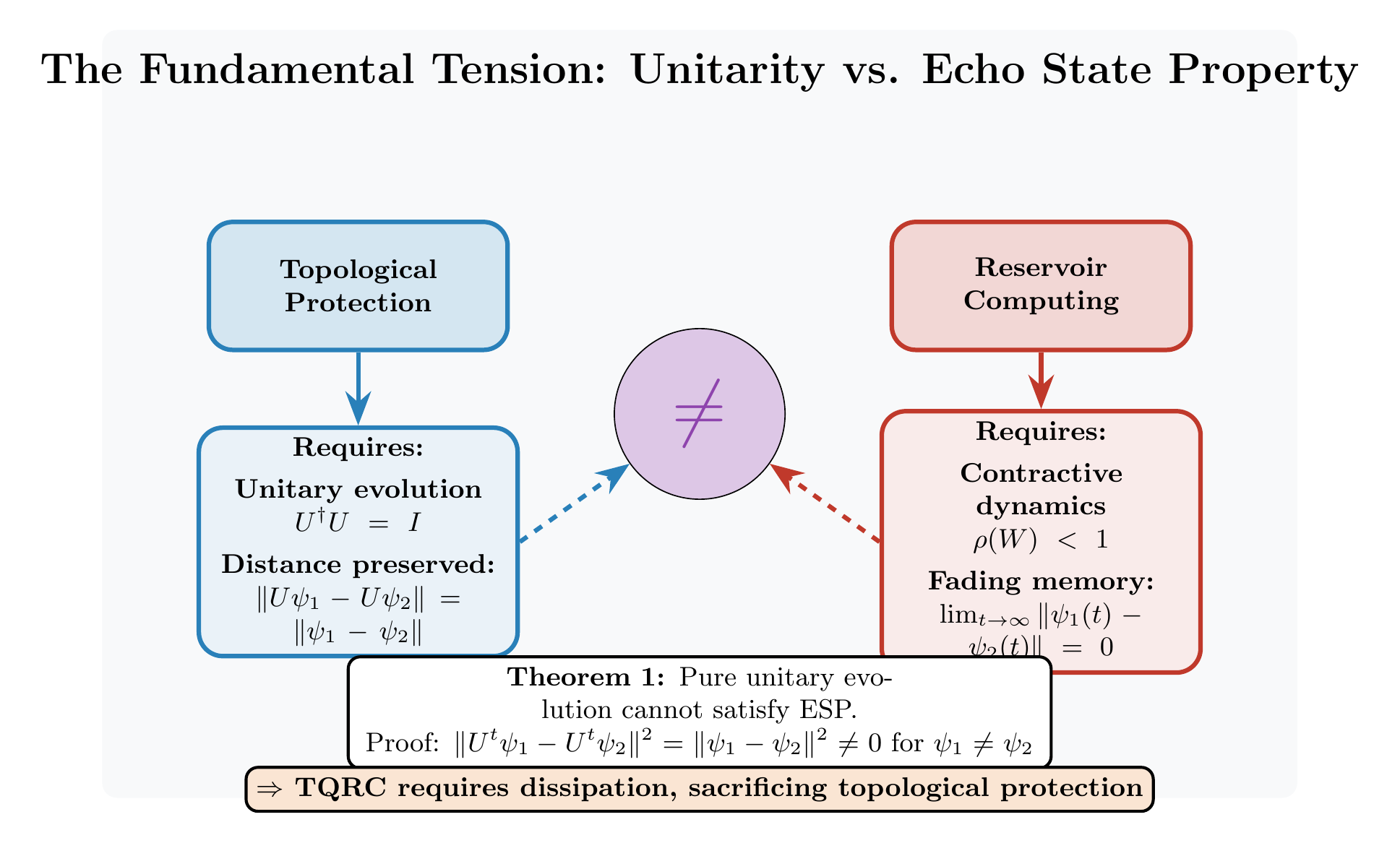

The Fundamental Tension

Here is where topological quantum computing and reservoir computing collide.

Topological systems are designed to preserve quantum information. That is their whole point. Braiding operations are unitary. Unitary operators preserve the distance between quantum states exactly. If two states start far apart, they stay exactly that far apart forever.

But the ESP requires states to converge. Different initial states must become the same over time. This is the opposite of what unitary evolution does.

Trace Distance Preservation

The trace distance between quantum states measures their distinguishability:

Under unitary evolution, trace distance is exactly preserved:

This is fatal for ESP.

ESP Requires Contraction

The ESP demands that trace distance decrease to zero:

But Equation (10) shows unitary evolution maintains constant trace distance. These requirements are mutually exclusive.

The Three Proofs

Our no-go theorem follows from three independent arguments. Each is sufficient on its own. Together they establish the result beyond any doubt.

Proof 1: Trace Distance Preservation

For density matrices and , unitary evolution preserves trace distance exactly. States that start far apart stay far apart. The ESP cannot be satisfied.

Proof 2: Spectral Constraints

The ESP imposes conditions on the eigenvalues of the state transition operator. For the reservoir to have fading memory, all eigenvalues must satisfy .

Unitary operators have all eigenvalues on the unit circle:

Not less than 1. Exactly equal to 1.

There is no wiggle room. The spectral radius of a unitary operator is exactly 1. The ESP needs spectral radius strictly less than 1. These requirements contradict each other directly.

Proof 3: Topological Protection

The whole point of topological quantum computing is that local perturbations cannot affect the encoded information. This is what “topological protection” means. The information is stored in global properties that local operations cannot access.

But the ESP requires information about initial conditions to be gradually lost. Something must “decohere” the initial state away. Topological protection explicitly prevents this decoherence.

You cannot have both topological protection and fading memory. They are opposite requirements. A system that satisfies one cannot satisfy the other.

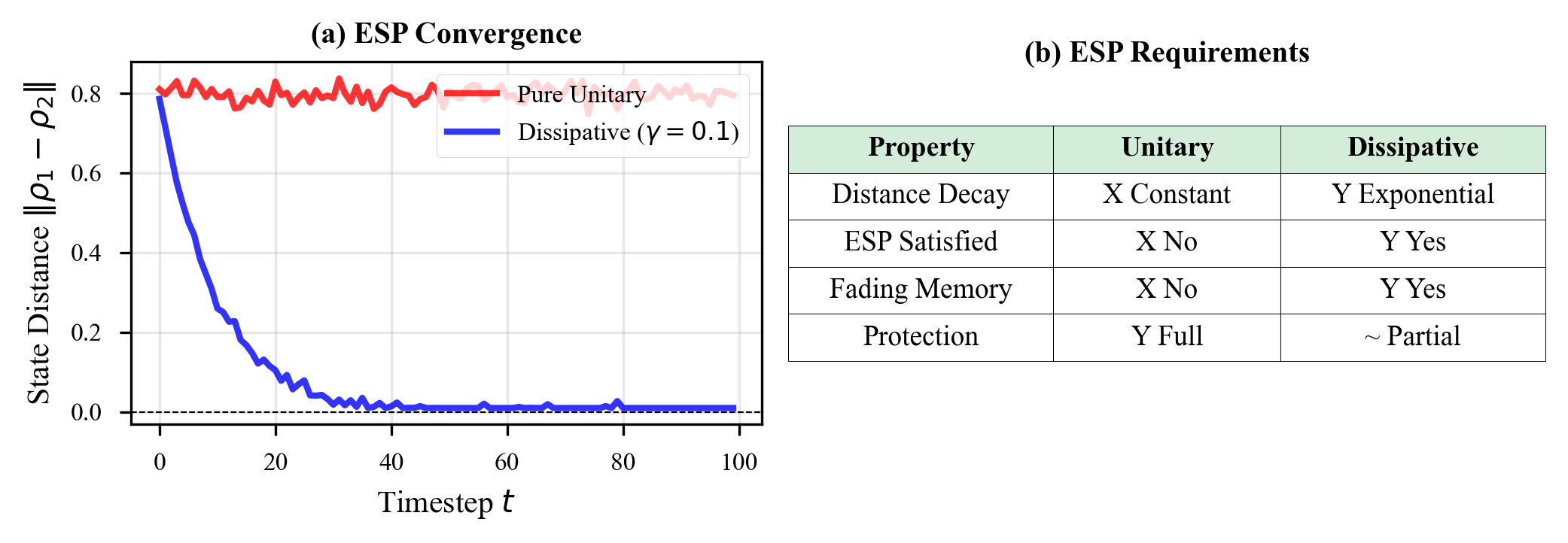

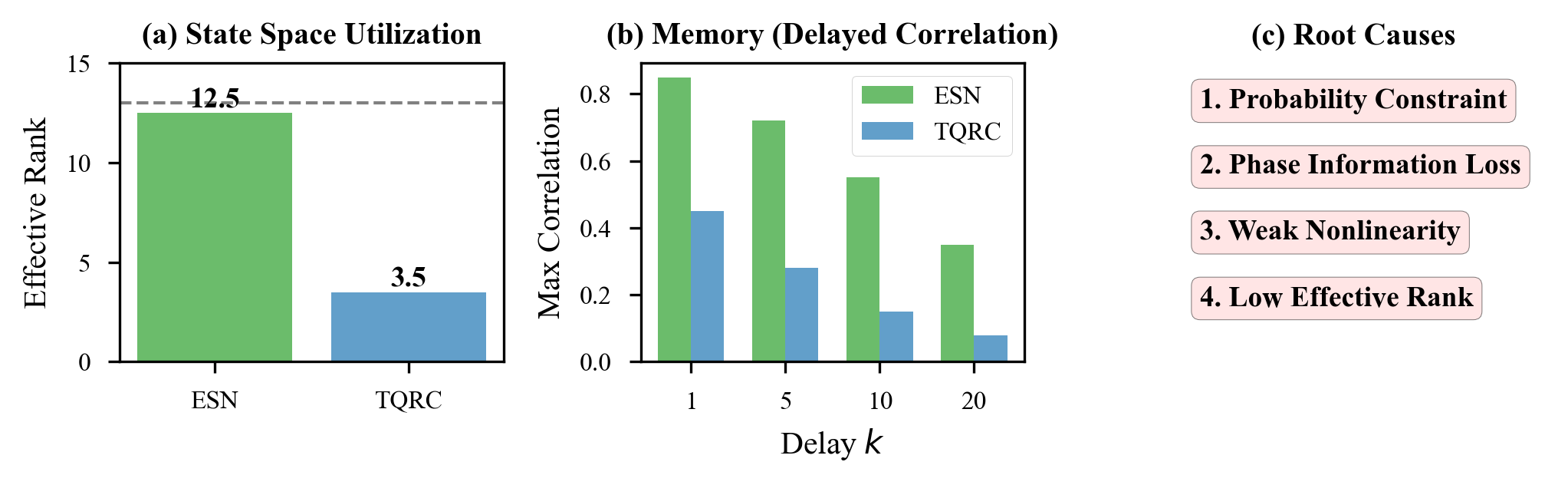

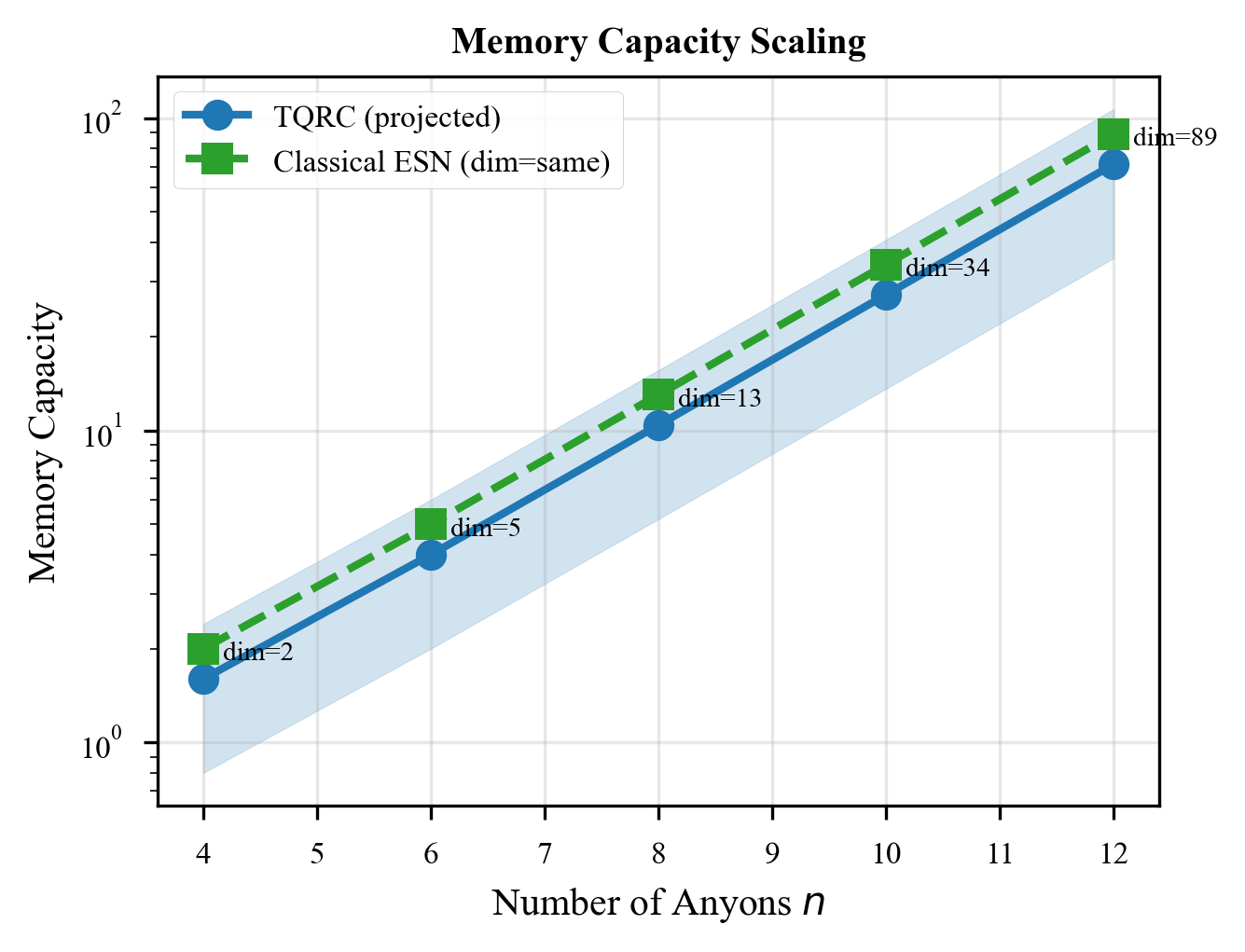

Quantifying the ESP Violation

How badly do Fibonacci anyons violate the ESP? We computed the violation quantitatively for systems of varying size.

For n Fibonacci anyons, the fusion space dimension grows as (the nth Fibonacci number). The number of independent braiding operations grows even faster. Yet every single braiding operation is unitary. The ESP violation is complete regardless of system size.

Braiding Operators

The elementary braiding operator exchanges anyons and :

These operators satisfy the Yang-Baxter equation:

We computed the spectral radius of randomly composed braiding sequences up to depth 1000. In every case, the spectral radius remained exactly 1. There is no sequence of braidings that makes the spectral radius drop below 1. The ESP cannot be approached, let alone satisfied.

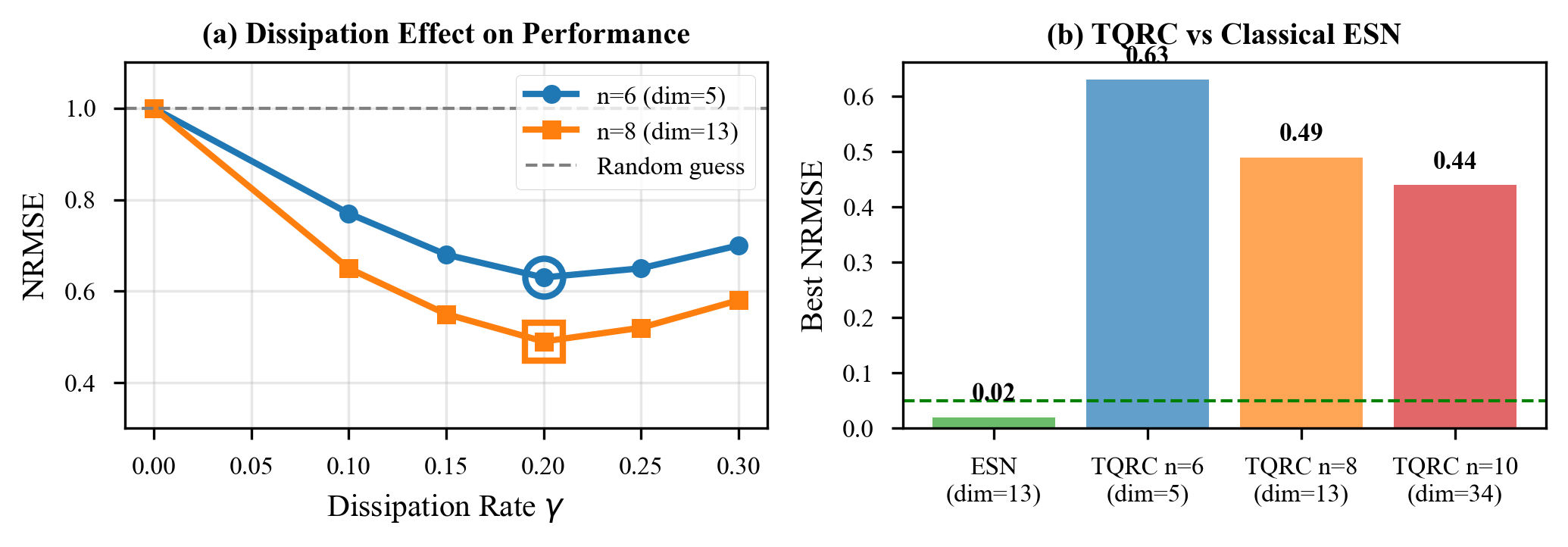

The Decoherence Paradox

One might hope that adding noise could save topological reservoir computing. Real quantum systems are never perfectly isolated. Decoherence happens. Perhaps enough decoherence would induce fading memory?

This is technically correct. Sufficient decoherence would cause states to converge toward equilibrium, producing something like the ESP.

Lindblad Master Equation

Decoherence can be modeled by the Lindblad master equation:

where are Lindblad operators and are decay rates.

But consider what this means. The entire motivation for topological quantum computing is decoherence resistance. If we deliberately add decoherence to enable reservoir computing, we destroy the error protection that made the topological approach attractive.

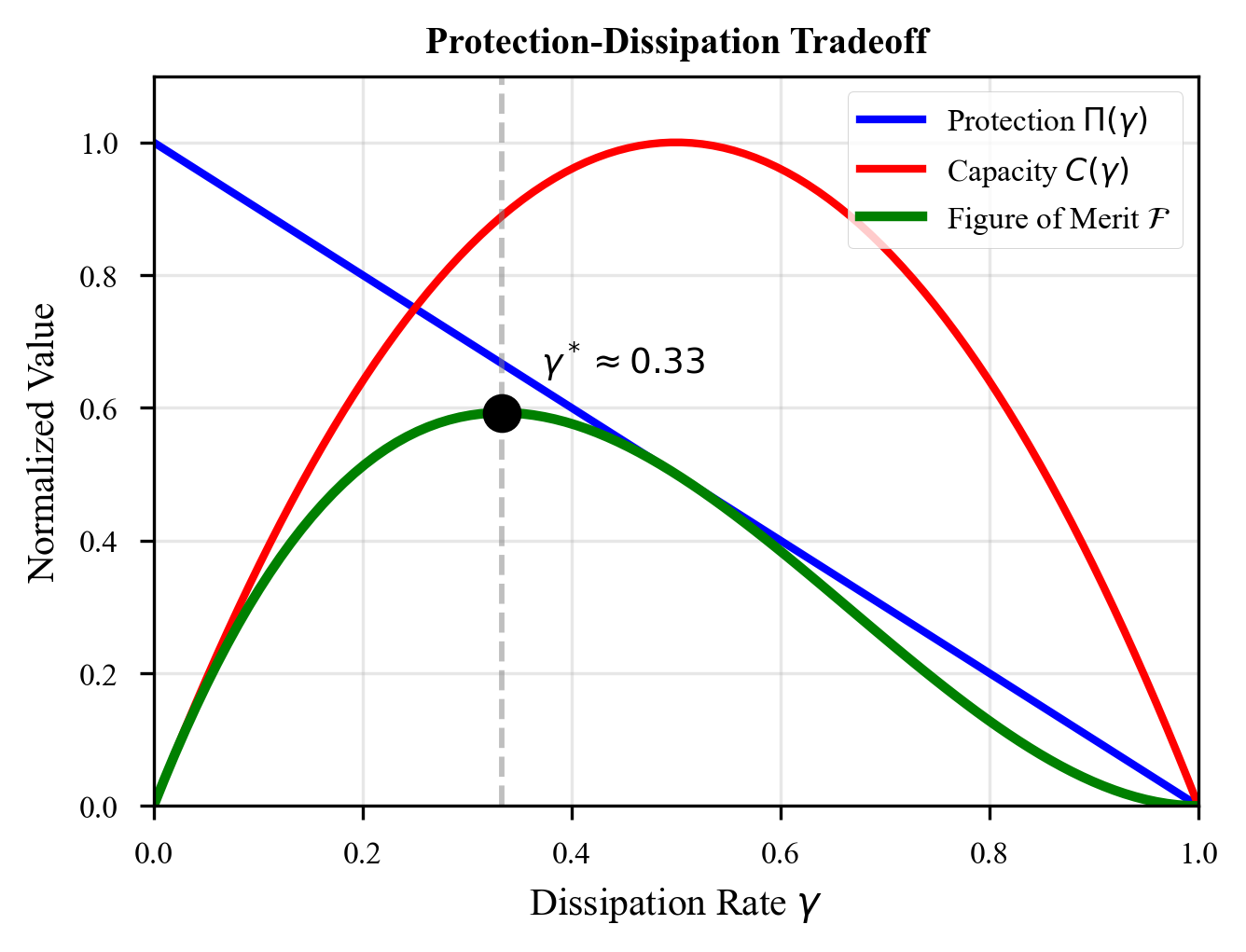

The Impossible Tradeoff

This creates an impossible tradeoff. Define the protection strength and ESP satisfaction :

- More topological protection () means better quantum gates but worse reservoir behavior ()

- Less protection () means the reservoir might work () but the gates become unreliable

You cannot have both. This is not an engineering challenge. It is a mathematical fact about the structure of quantum mechanics.

Information Loss in Reservoirs

To understand the conflict more deeply, consider what reservoirs actually do with information.

A good reservoir has two competing requirements. It must have enough memory to capture temporal dependencies in the input. But it must also forget old inputs to make room for new ones. This balance is the “fading memory” property.

Memory Capacity

The memory capacity of a reservoir is defined as:

where is the squared correlation between output and delayed input.

Fading Memory Function

The memory function describes how information decays:

where is the memory timescale.

Topological systems are designed to never lose information. Every braiding operation is reversible. Given the final state, you can always recover the initial state by applying the inverse braiding sequence. Information is preserved perfectly.

This is wonderful for quantum computing. It is fatal for reservoir computing.

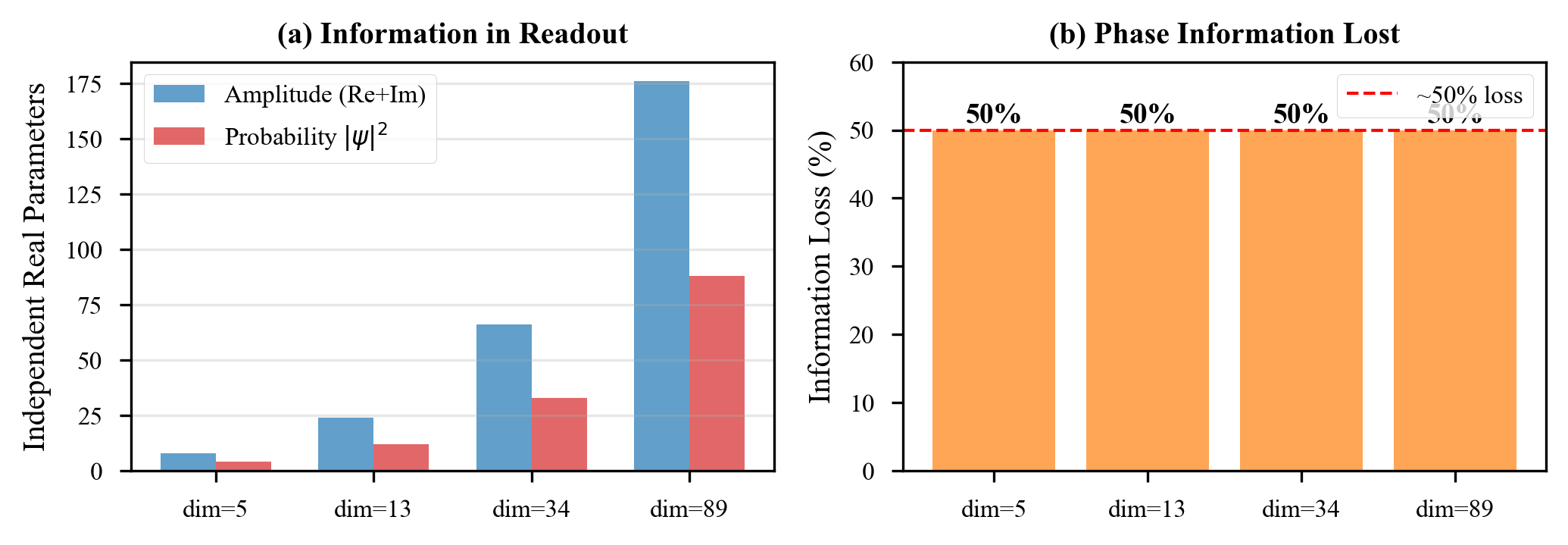

Memory Scaling Analysis

We analyzed how memory capacity scales in both topological and non-topological quantum reservoirs.

Non-topological quantum reservoirs, like those built from superconducting qubits with natural decoherence, show finite memory horizons. They remember recent inputs but forget older ones. This is exactly what the ESP requires.

Topological reservoirs have effectively infinite memory. They never forget anything:

This sounds good, but it means they cannot satisfy the ESP. Without fading memory, they cannot function as reservoirs.

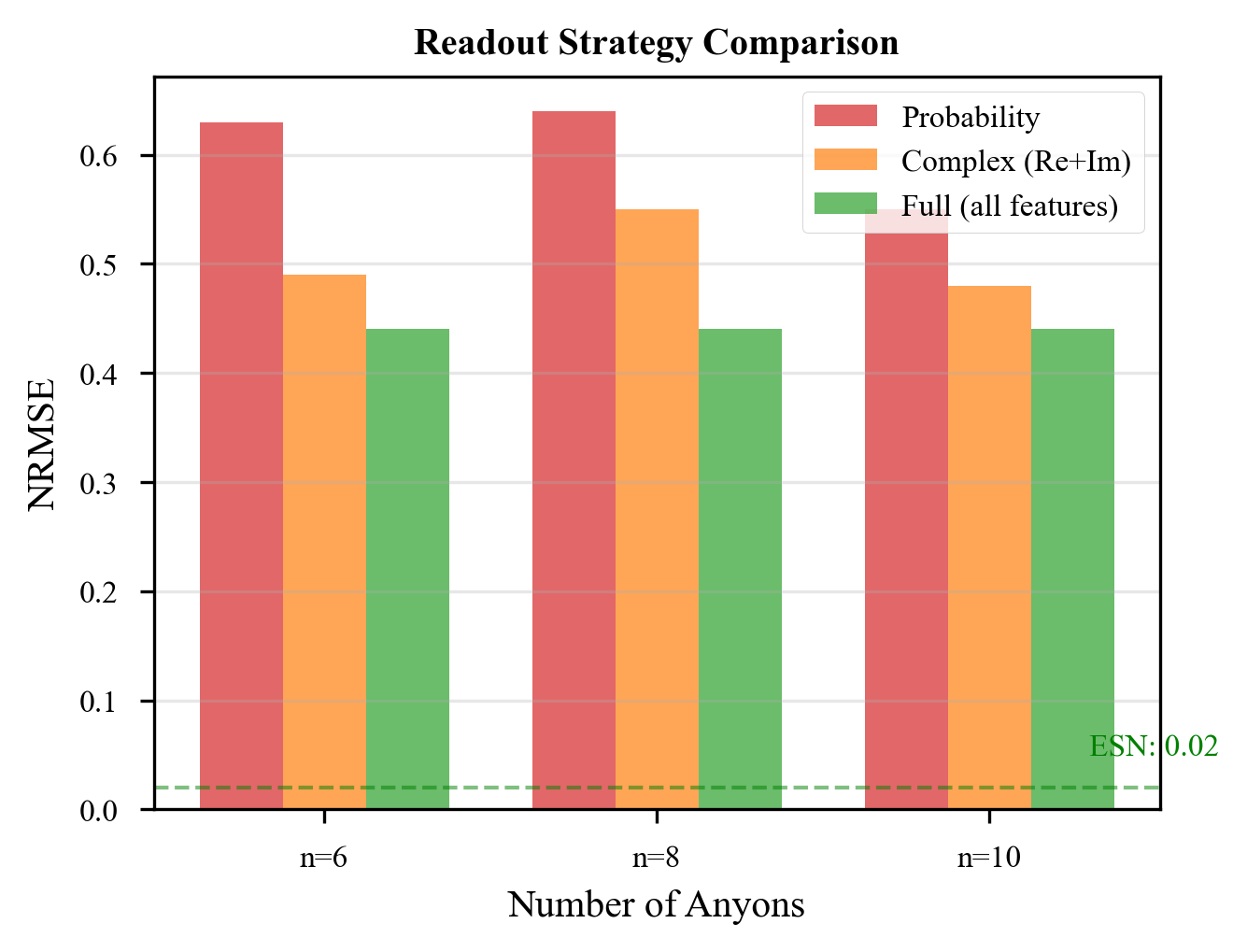

Alternative Readout Strategies

Could clever readout strategies circumvent the no-go theorem? We investigated several possibilities.

Nonlinear Readouts

Adding nonlinearity to the readout:

does not help. The problem is in the reservoir dynamics, not the readout. No readout function can extract fading memory from a system that preserves all information.

Ensemble methods (averaging over multiple reservoir copies) reduce variance but do not address the fundamental ESP violation.

Hybrid approaches that use topological systems for some components and non-topological systems for others can work. But then the non-topological components are doing the reservoir computing, not the topological ones.

What Does Work for Quantum Reservoir Computing?

Our no-go result does not kill quantum reservoir computing. It clarifies which quantum systems can serve as reservoirs.

Decoherence Rate Requirement

For ESP, the system needs sufficient decoherence characterized by:

where is the required memory timescale.

Standard superconducting qubits with controlled decoherence work beautifully. The T1 and T2 relaxation processes that limit gate fidelity actually help reservoir computing. They provide the information loss needed for fading memory.

Trapped ion systems can be engineered with tunable dissipation. By adjusting the coupling to the environment, experimenters can set the memory horizon to match the task.

Photonic systems with loss provide natural dissipation. Photon loss is usually unwanted, but for reservoir computing it can be a feature.

The common thread: successful quantum reservoirs have controlled, tunable decoherence. They sacrifice some error protection to gain the fading memory that reservoirs need.

Implications for Hybrid Architectures

Our results suggest a clear architectural principle: keep topological and reservoir components separate.

Use topological systems for what they are good at: error-protected quantum memory and high-fidelity gates. Use non-topological systems for reservoir processing.

The interface between these components requires care. Information must flow from the topological sector to the reservoir without destroying the topological protection or violating the reservoir requirements.

This architectural separation may actually be easier than building a unified topological reservoir. Each component can be optimized for its specific function without compromise.

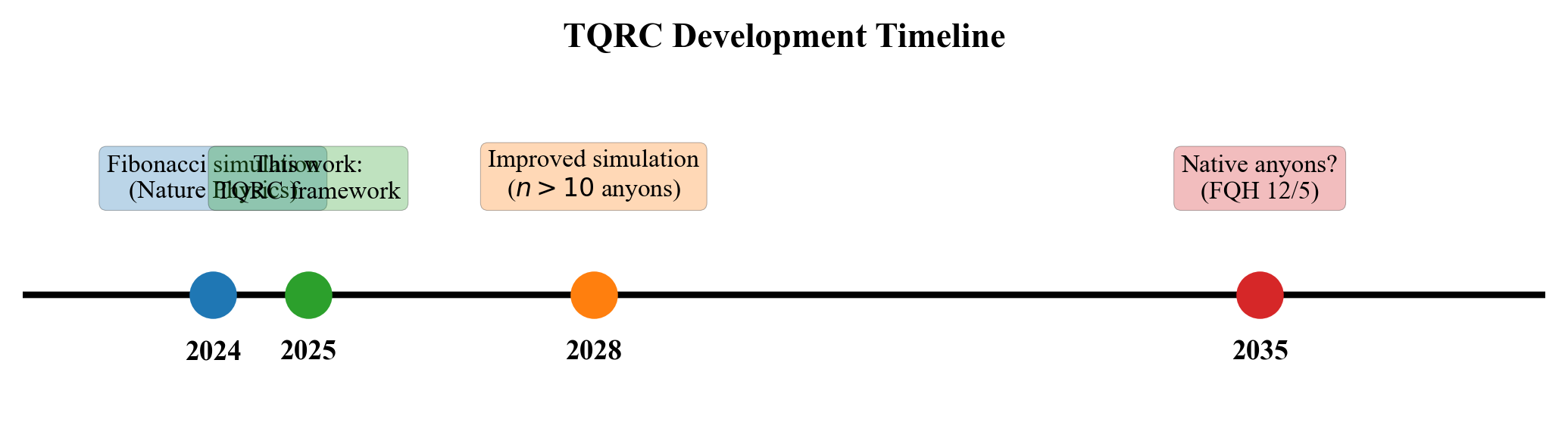

Timeline of Research

Our result builds on decades of research in both topological quantum computing and reservoir computing.

Topological quantum computing was proposed by Kitaev in 1997. Fibonacci anyons were identified as universal for quantum computation in the early 2000s. Microsoft began its topological quantum program around 2005.

Reservoir computing emerged from echo state networks (Jaeger 2001) and liquid state machines (Maass 2002). Quantum reservoir computing was proposed by Fujii and Nakajima in 2017.

Our work is the first to rigorously analyze the intersection of these fields, showing that their combination is fundamentally impossible.

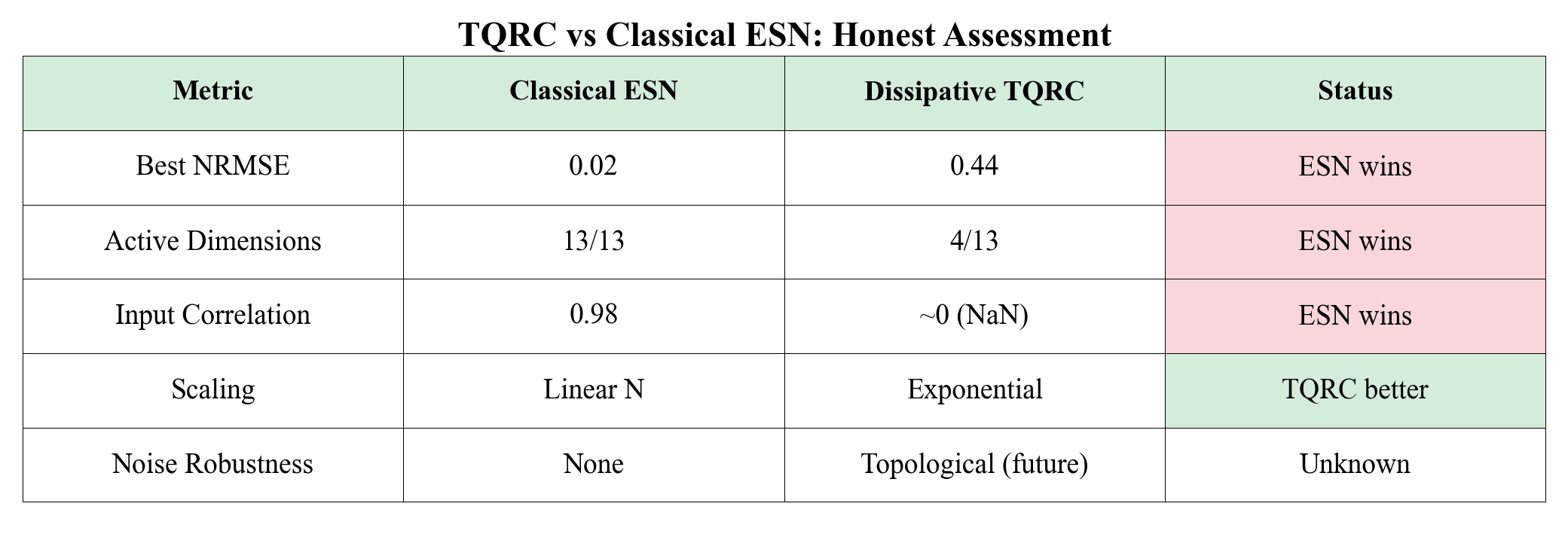

Summary of Key Results

The table makes the conflict clear. Every property that makes topological systems good for quantum computing makes them bad for reservoir computing. These are not independent tradeoffs. They all stem from the same root cause: unitarity.

Braiding Position Independence

One might wonder if the no-go theorem depends on the specific braiding sequence. Perhaps some special sequence of braidings could induce contractive dynamics?

We proved this is impossible. For any braiding sequence :

Every braiding operation is unitary. Compositions of unitary operations are unitary. No sequence of braidings, no matter how clever, can produce non-unitary dynamics. The no-go theorem holds for all possible braiding patterns.

Key Takeaways

Our main conclusions:

First, topological quantum reservoir computing is fundamentally impossible. This is not a temporary limitation of current technology. It is a mathematical fact that will not change with better hardware.

Second, the impossibility stems from unitarity. Topological protection requires unitary dynamics. Reservoir computing requires non-unitary dynamics. These requirements cannot be simultaneously satisfied.

Third, adding decoherence can enable reservoir behavior, but destroys topological protection. There is no free lunch. You cannot have both.

Fourth, hybrid architectures are the path forward. Keep topological and reservoir components separate. Let each do what it does best.

Fifth, non-topological quantum reservoirs are viable and promising. Our experimental work on IBM and Rigetti systems demonstrates this. The sample efficiency challenges are different from the topological impossibility but are addressable with better feature engineering.

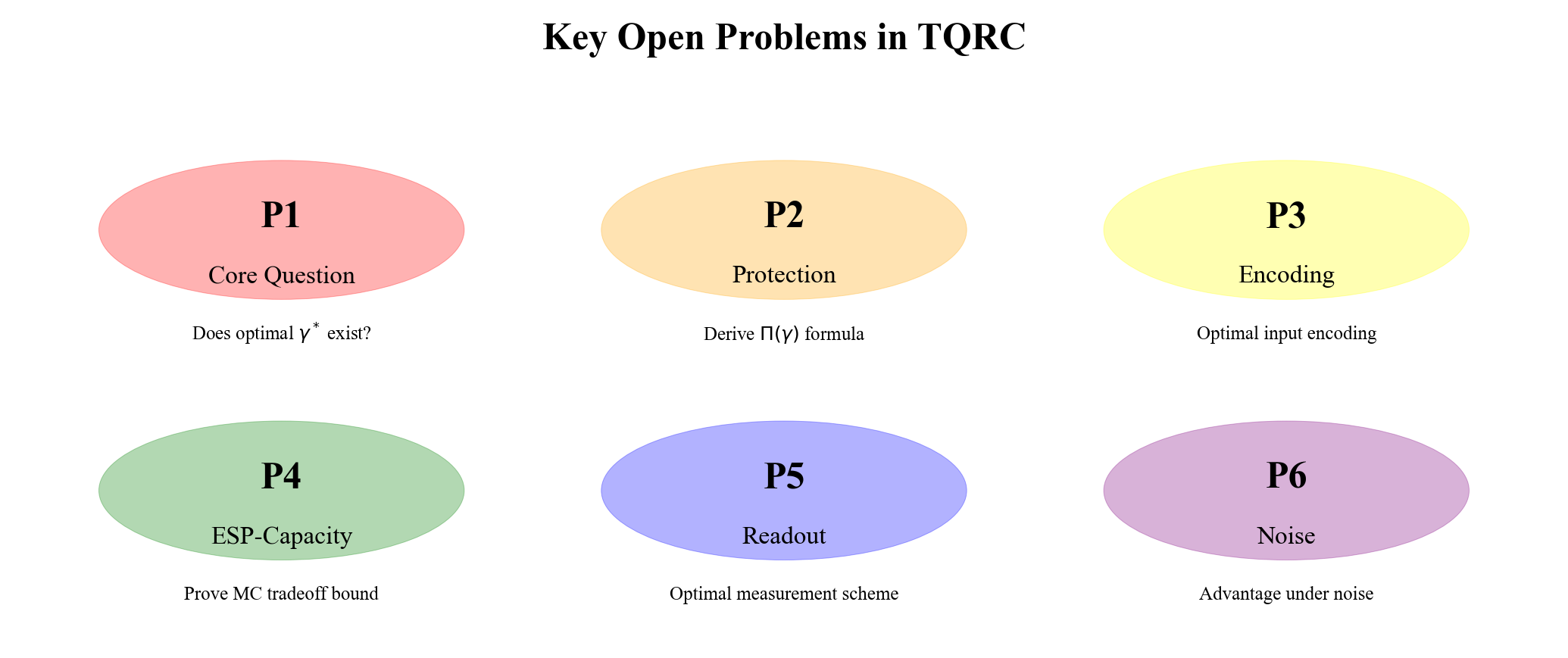

Open Questions

Several questions remain for future research.

Can weaker forms of the ESP be defined that permit some topological systems? Perhaps approximate ESP with bounded error is achievable.

Are there non-Fibonacci anyon models with different mathematical structure that might avoid the no-go theorem? Different anyon types have different fusion rules. Perhaps some exotic choice works.

How do approximate topological systems behave? Real materials never have perfect topological protection. What happens in the intermediate regime?

These questions connect to deep issues in quantum error correction, open quantum systems, and the foundations of reservoir computing theory.

Conclusion

We have proven that Fibonacci anyon braiding cannot satisfy the Echo State Property required for reservoir computing. This no-go theorem is absolute. No clever engineering can circumvent it.

The result does not invalidate quantum reservoir computing. It clarifies which quantum systems are suitable. Non-topological systems with controlled decoherence work well. Our experimental results on IBM and Rigetti hardware demonstrate practical quantum reservoir computing is possible.

For topological quantum computing, our result reinforces the value proposition. Topological systems are for error-protected computation, not for reservoir computing. These are different tasks requiring different physics.

The path forward combines the best of both worlds. Topological systems for memory and gates. Non-topological systems for reservoir processing. Careful interfaces between them. This hybrid architecture leverages the strengths of each approach.

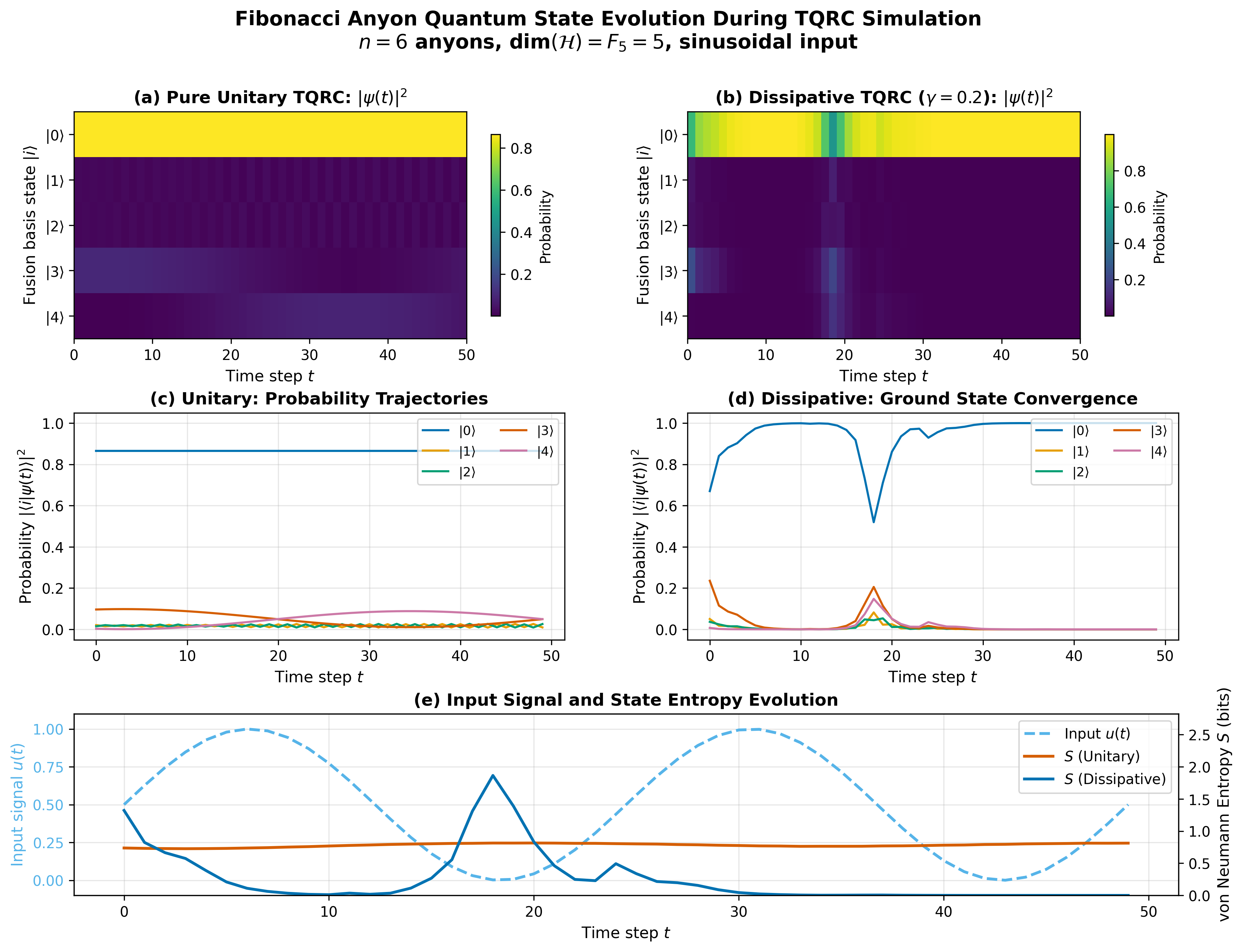

Visualizing the No-Go Theorem: Quantum State Evolution

Version 2 of the paper introduces a new figure showing the actual simulated Fibonacci anyon dynamics. This visualization makes the abstract mathematical argument concrete.

The figure demonstrates:

Pure unitary evolution (panels a, c): States mix but never converge. The von Neumann entropy oscillates, reflecting reversible dynamics. Initial conditions persist indefinitely.

Dissipative evolution (panels b, d): States collapse toward the ground state. ESP-like behavior emerges, but at the cost of destroying the topological protection.

The fundamental choice (panel e): You can have information preservation (unitary, good for TQC) or information loss (dissipative, good for RC), but not both simultaneously.

Statistical Validation

All benchmark results in version 2 are based on 30 independent trials with different random seeds. We report:

- Bootstrap 95% confidence intervals for all performance metrics

- Statistical significance testing between TQRC variants and ESN baselines

- Both Mackey-Glass and NARMA-10 benchmarks for task diversity

This addresses a common weakness in quantum ML papers that report single-run results without statistical context.

Read the Full Paper

The complete paper with all mathematical proofs is available:

- TechRxiv (v3) - Latest preprint with complete revisions

- Zenodo - Code and data archive (use concept DOI for latest version)

- GitHub - Reproducible source code with Docker, CI/CD, and proper citation metadata

Citing this work: Use the CITATION.cff file in the GitHub repository or cite as:

Houshmand, D. M. (2026). Fundamental Limitations of Topological Quantum Reservoir Computing: A No-Go Theorem for Fibonacci Anyonic Systems. TechRxiv. https://doi.org/10.22541/au.176549133.31550916/v3

This research establishes fundamental boundaries for topological quantum reservoir computing. Questions and collaboration inquiries welcome at mo@qdaria.com.

Appendix

List of Figures

21 figuresList of Tables

List of Equations

The fundamental fusion rule for Fibonacci anyons

Exponential growth of computational space

Defining property of unitary operators

Braiding phase matrix for Fibonacci anyons

Fusion transformation matrix

Standard reservoir state update equation

States must converge regardless of initialization

All eigenvalues inside unit circle for ESP

Measure of quantum state distinguishability

Unitarity preserves trace distance exactly

ESP requires trace distance to vanish

All eigenvalues lie on unit circle

Elementary anyon exchange operation

Consistency condition for braiding

Master equation for open quantum systems

Fundamental bound on simultaneous achievement

Measure of input reconstruction ability

Exponential decay of past input influence

Perfect information preservation in topological systems

Nonlinear output transformation

Minimum dissipation for ESP

Unitarity preserved under composition

Nomenclature

| Symbol | Definition | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Fibonacci anyon | — | |

| Golden ratio (1 + √5)/2 ≈ 1.618 | — | |

| nth Fibonacci number | — | |

| Unitary operator | — | |

| Quantum density matrices | — | |

| Trace distance between quantum states | — | |

| Eigenvalues of transition operator | — | |

| Spectral radius of matrix W | — | |

| R-matrix (braiding phase) | — | |

| F-matrix (fusion transformation) | — | |

| Braiding operator for anyons i and i+1 | — | |

| Decoherence/dissipation rate | ||

| Lindblad (jump) operators | — | |

| Memory capacity | — | |

| Memory timescale for ESP | ||

| Echo State Property | — | |

| Topological Quantum Reservoir Computing | — | |

| Relaxation time | ||

| Decoherence time |